Yung-Hsueh Huang describes his Bold Lift strategy for long-lasting results and reduced downtime when addressing deficient skeletal support

20 Skin Clinic Taichung City, Xitun Taiwan

Facial ageing involves simultaneous changes to bones, subcutaneous tissues, muscles, skin and retaining ligaments(1) that cause skin atrophy, sagging, wrinkles, skeletal resorption, and fat compartment redistribution(1,2). During the ageing process, the skin, superficial and deep subcutaneous tissue, superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS), deep fascia, and bone(3), each adapt to decreasing strength, volume and elasticity, causing tissue and pigmentation changes, hollowness and laxity(4,5). However, facial fillers can correct ageing-related indications and volume loss non-surgically(2,6), and can produce long-lasting, optimal results with reduced invasiveness and downtime(7).

The author devised the Bold-Lift strategy for the pan-facial injection of calcium hydroxyapatite fillers (CaHA, Radiesse®; Merz North America, NC, USA). CaHA’s rheology facilitates its precise placement within resorbed bony areas to resolve deficient skeletal support, exaggeration of contour irregularities and sagging due to receding of the piriform fossa, cheekbone flattening, and maxilla and mandible atrophy.

Case presentation

Six patients without comorbidities, aged 30–40 years, self-presented with a tired appearance, diagnoses of bone resorption and fat compartment redistribution, and consented to receive CaHA injections for facial volume loss using the Bold Lift technique.

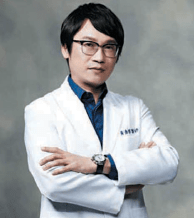

(A) Injection points and desired directional improvements.

(B) Patient is shown from frontal and oblique angles before treatment.

(C) 3 months after treatment.

The patients had varying initial levels of aesthetic deficiency and were assessed according to the validated Merz Aesthetic Scale (MAS) for Upper Cheek8 and Brow Positioning9. For the treatment, CaHA was diluted 5:1 with 2%-lidocaine. Seven injection points were identified, one per eyebrow arch, lateral eyebrow, lateral zygoma, piriform fossa and chin, and two in the anteromedial cheek. Filler boluses were injected in the supraperiosteal plane. For the eyebrow arch, 0.3mL of CaHA was injected using a 25 G needle (25 mm). A 25 G needle (25 mm) was used to inject 0.2–0.3mL of CaHA into the lateral eyebrow, lateral zygoma and anteromedial cheek. The anteromedial cheek was palpated and the infraorbital foramen (IOF) was injected. Finally, the piriform fossa and the chin each received 0.2–0.3 mL of CaHA with a 25 G needle (23 mm). Chin fillers were injected below the mentalis muscle. Ultimately, all patients received 3.6 mL of filler.

“Patients were evaluated at rest as well as before and after treatment, using the MAS and the Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS).”

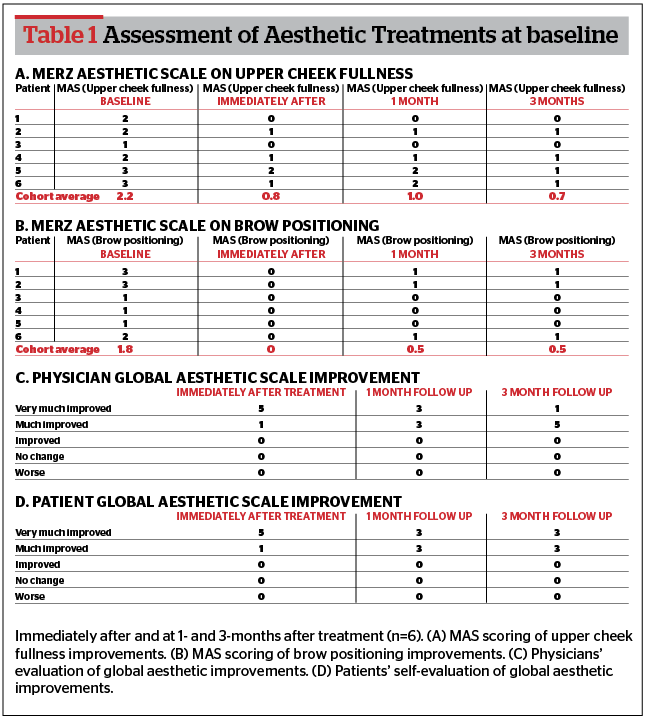

Patients were evaluated at rest as well as before and after treatment, using the MAS and the Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS). These ratings were reinforced with standardised photos taken at rest, pre-injection, immediately, 1- and 3-months post-injection, from the frontal angle, 45° from the left and right oblique angles, and from the left and right profiles. The level of improvements for brow positioning (at rest), as well as physician (Table 1) and patient GAIS, were measured at follow-up. Patients who achieved 1 point of improvement in the MAS for upper cheek fullness (at rest) were analyzed for this report. All patients gave their informed consent.

“In the author’s study, although pan-facial improvement was the goal, only brow positioning and upper cheek fullness were graded because validated quantitation scales for full-face assessments do not exist. “

Patients rated ‘1’ to ‘2’ on the Upper Cheek scale had ‘ideal’ faces with mild-to-moderate upper cheek hollowness, and required one treatment for satisfactory-to-good results. Those rated ‘1’ to ‘3’ on the Brow Positioning scale and ‘3’ to ‘4’ on the Upper Cheek scale had medium-to-flat eyebrow arches and required two treatments with a 3-month interval. At 3-months follow-up (Table 1) without touch-up, all patients had at least 1 MAS improvement point in upper cheek fullness at rest, with mean scores at baseline, immediately post-treatment, and 1-month and 3-months post-treatment of 2.2, 0.8, 1.0, and 0.7, respectively. All patients also demonstrated at least 1 MAS improvement point in brow-positioning from the baseline at all timepoints, with mean scores at baseline, immediately post-treatment, and at 1-month and 3-months post-treatment of 1.8, 0, 0.5 and 0.5, respectively. At all follow-up timepoints, improvements were reported as ‘Much Improved’ or ‘Very Much Improved’. The cohort’s treatment outcomes are demonstrated here in the results of one patient (Figure 1).

Discussion

Minimally-invasive procedures produce multifactorial outcomes. First, a more natural, refreshed and youthful appearance is created10. Second, a stratified approach selects for the most appropriate treatments through a careful diagnosis of clinical changes in facial anatomy and dermatological problems11. Third, blunt-tip cannulas are used to reduce tissue damage and expedite recovery. Finally, they are cost-effective and give high levels of patient satisfaction12. In devising the Bold-Lift injection technique, we sought to include these outcomes within a single procedure for holistic, whole-face improvements. CaHA’s rheological properties are due to its high viscosity and G’, which impart a desirable elasticity and versatility. We leveraged its high viscoelasticity to structurally replace bone resorbed during physiological ageing and produce visible lifting. Its high viscosity keeps it in place during injection, while a high G’ confers resistance to deformation despite the shear forces inherent to natural physiological activities, including muscular contraction. These characteristics make CaHA fillers (Radiesse®) ideal for the technique devised in our Bold-Lift injection. Moreover, CaHA, when hyperdiluted, also produces collagen and elastin, leading to a skin-tightening effect(13).

“The Bold-Lift leveraged CaHA’s high viscoelasticity to replace bone resorption and increase and strengthen deficient structural supports, resulting in a visible and much-requested facial lifting effect.”

In the author’s study, although pan-facial improvement was the goal, only brow positioning and upper cheek fullness were graded because validated quantitation scales for full-face assessments do not exist. In the author’s representative patient, placing fillers in the supraperiosteal plane of her eyebrow arch lifted it. Fillers in her lateral eyebrow, lateral zygoma, and anteromedial cheek lifted her eyebrow laterally, and also lifted her midface and cheek while redefining the cheek apex. Fillers lifted the piriform fossa and released her nasolabial fold, while chin fillers improved her mental crease and supported her chin contour. The patient achieved a visible lift at the outer eye corner, greater anterior anteromedial cheek projection and a more prominent and smoother (less dimpled) chin. Immediately post-injection, the eyebrow and lateral canthus angle lifted and the anteromedial cheek area was more projected. Similar levels of improvements were observed in all six patients (Table 1). Although no severe adverse events were observed, all patients treated with this protocol experienced mild swelling, ecchymosis, and erythema immediately post-injection that resolved within two days without treatment. At 1- and 3-months post-treatment, no long-term complications occurred. To the author’s knowledge, there is only one other description of a similar treatment with CaHA for face volumisation; however, a different set of injection points and cannula or needle were used(14). The author adds to this knowledge by demonstrating a further set of injection points and simplifying processes by using just needles to achieve the patient’s desired outcomes.

Conclusions

The Bold-Lift technique is best used at treatment initiation to create the framework for soft tissue augmentation and contouring. Although no severe adverse events were observed, patients may experience post-injection swelling, erythema and ecchymosis. The Bold-Lift leveraged CaHA’s high viscoelasticity to replace bone resorption and increase and strengthen deficient structural supports, resulting in a visible and much-requested facial lifting effect.

Declaration of interest The author declares no conflict of interest

Acknowledgment The author expresses their appreciation to Merz Asia Pacific Pte Ltd Taiwan Branch for funding the preparation of this manuscript, and Shawna Tan, for manuscript writing and editorial assistance

Funding/Financial disclosures Yung-Hsueh Huang received an honorarium from Merz to conduct the study. All authors had full access to the study data and had final responsibility for the decision to publish. Editorial assistance, funded by Merz Asia Pacific Pte. Ltd. (Taiwan Branch), was provided by Shawna Tan. The preparation of this manuscript was sponsored by Merz Asia Pacific

Figure 1 © Yung-Hsueh Huang

Table 1 © Yung-Hsueh Huang

References

- Wulc AE, Sharma P, Czyz CN. The Anatomic Basis of Midfacial Aging. In: Hartstein M, Wulc A, Holck D. Midfacial rejuvenation. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2012

- Sundaram H, Voigts B, Beer K, Meland M. Comparison of the rheological properties of viscosity and elasticity in two categories of soft tissue fillers: calcium hydroxylapatite and hyaluronic acid. Dermatol Surg. 2010 Nov;36 Suppl 3:1859-65

- Wong CH, Mendelson B. Newer Understanding of Specific Anatomic Targets in the Aging Face as Applied to Injectables: Aging Changes in the Craniofacial Skeleton and Facial Ligaments. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov;136(5 Suppl):44S-48S

- Ramanadham SR, Rohrich RJ. Newer Understanding of Specific Anatomic Targets in the Aging Face as Applied to Injectables: Superficial and Deep Facial Fat Compartments–An Evolving Target for Site-Specific Facial Augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov;136(5 Suppl):49S-55S

- Wong CH, Mendelson B. Newer Understanding of Specific Anatomic Targets in the Aging Face as Applied to Injectables: Aging Changes in the Craniofacial Skeleton and Facial Ligaments. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov;136(5 Suppl):44S-48S

- Greco TM, Antunes MB, Yellin SA. Injectable fillers for volume replacement in the aging face. Facial Plast Surg. 2012 Feb;28(1):8-20

- Edelson KL. Hand recontouring with calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse®). J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8:44–51

- Carruthers J, Flynn TC, Geister TL, et al. Validated assessment scales for the mid face. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(2 Spec No.):320–332

- Flynn TC, Carruthers A, Carruthers J, et al. Validated Assessment Scales for the Upper Face. Dermatol Surg. 2012; 38:309-319.

- Maisel A, Waldman A, Furlan K, et al. Self-reported Patient Motivations for Seeking Cosmetic Procedures. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Aug 15

- Chao YYY, Chhabra C, Corduff N, et al. PAN-ASIAN CONSENSUS-Key Recommendations for Adapting the World Congress of Dermatology Consensus on Combination Treatment with Injectable Fillers, Toxins, and Ultrasound Devices in Asian Patients. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017 Aug;10(8):16-27

- Sobanko JF, Taglienti AJ, Wilson AJ, et al. Motivations for seeking minimally invasive cosmetic procedures in an academic outpatient setting. Aesthet Surg J. 2015 Nov;35(8):1014-20

- Chao YY, Kim JW, Kim J, et al. Hyperdilution of CaHA fillers for the improvement of age and hereditary volume deficits in East Asian patients. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology. 2018;11:357-363