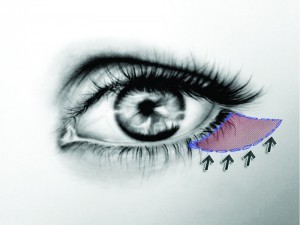

Rejuvenation of the lower eyelid often requires tightening of excess skin and removal or transposition of orbital fat. Although transcutaneous lower-lid blepharoplasty accomplishes these aesthetic demands, it has been associated with an increased risk of lower-lid malposition rates of up to 20%. The mini-lift technique allows the surgeon to sculpt the orbital fat prolapse and address excess skin, avoiding the traditional complications of transcutaneous lower-lid blepharoplasty, such as scleral show, rounded lateral canthus, and ectropion.

Cosmetic eyelid surgery has the benefit of 2000 years of development and refinement of surgical techniques and instruments. Ali Ibn Isa (AD 940–1010) first described the procedure more than 1000 years ago1,2. Aulus Cornelius Celsus, the first century Roman encyclopaedist and philosopher, was likely the first to comment on the excision of skin of the upper eyelids when he described the treatment of the ‘relaxed eyelid’ in De re Medica3, which was published only in 1478 following its rediscovery by Pope Nicholas V.

The term ‘blepharoplasty’ (from the Greek words blepharon, ‘eyelid’, and plassein, ‘to form’) was originally used by Von Graefe in 1818 to describe a case of eyelid reconstruction that he had performed in 18094. In the 1913 edition of the American Encyclopedia of Ophthalmology, blepharoplasty is defined as the reformation, replacement, readjustment or transplantation of any of the eyelid tissues5. Now, blepharoplasty refers to the excision of excessive eyelid skin, with or without the excision of orbital fat, for either functional or cosmetic indications. These cosmetic indications have been recognised by physicians only since the turn of the last century, but are now the most common reason for such surgery on the lower eyelids. This change followed the development of improved techniques, better surgical results, and control of sepsis, as well as the change in social attitudes.

Modern transcutaneous blepharoplasty was first described by Castañares in 19516, when an incision was made 1–2 mm below the eyelash line, allowing access to the orbicularis oculi muscle through a skin flap technique. This technique resulted in complications such as ectropion and a lateral rounding of the lower eyelid, but the procedure gradually evolved into the use of a skin muscle flap to allow access to the intraorbital fat.

McCollough and English7 further evolved the technique to a skin flap or skin muscle flap, in which the incision is placed inferiorly to the tarsal margin, thus allowing a ‘cuff’ of the pretarsal orbicularis oculi muscle to remain undisturbed. However, this technique is now rarely used.

Historically, the transcutaneous approach has been the surgical technique of choice, but often resulting in lower‑lid ectropion, noticeable scarring, and lower-lid retraction, the latter being the most common and dreaded complication. The transconjunctival technique was first described in 1924 by Julien Bourquet. This approach was popularised by Tessier8, who used the conjunctival approach to the orbital floor and maxilla in congenital malformation and trauma.

Anatomy

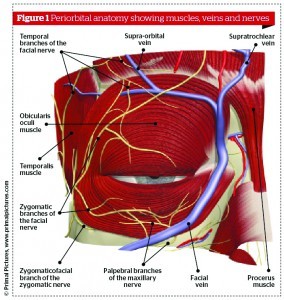

The lower eyelid is divided into an anterior lamella, being the skin and orbicularis, and a posterior lamella, being tarsus and conjunctiva. The tarsus of the lower lid is as long as the upper tarsus, but is only 4–5 mm wide at the centre of the lid. The tarsus has a number of meibomian glands with orifices on the ciliary border. The capsulopalpebral fascia in the lower lid is analogous to the levator aponeurosis of the upper lid. It originates from attachments to the terminal muscle fibres of the inferior rectus muscle. It divides as it encircles the inferior oblique muscle then joins to form Lockwood’s suspensory ligament. The capsulopalpebral fascia inserts into the inferior tarsal border and stands to the inferior conjunctival fornix, the suspensory ligament of the fornix.

The orbital septum—a multilayered thin sheet of fibrous tissue—arises from the perioteum over the inferior orbital rim. The orbital septum fuses with the capsulopalpebral fascia at or below the inferior tarsal border. It is the septum that divides the eyelid into anterior and posterior lamella. The anatomic significance of the septum orbitale is that it keeps the orbital fat in its posterior location. In transconjunctival blepharoplasty, the entrance into the orbital fat is made posterior to the orbital septum. Therefore, the anterior lamella is not disturbed.

The orbicularis muscle is divided arbitrarily into orbital and palpebral portions. The palpebral orbicularis muscle is divided into pretarsal and preseptal parts on the basis of underlying anatomic structure. There are voluntary and involuntary actions to the palpebral part of orbicularis muscle, and involuntary action to the orbital part.

Retraction may occur even if skin resection is conservative, as the retraction may result from pathological changes at a number of anatomic sites — for example, vertical shortening of the skin, postoperative scarring, contracture of tissue — but in the author’s experience scarring in the plane of the orbital septum is the most common cause of post-blepharoplasty eyelid retraction. When an upward traction of the lower lid is applied, it is difficult to spot a tethering of the mid-lamella. This is evidence of scarring in the plane of the septum, without evidence of skin shortage.