Complications

Complications or sequelae from placement of mandibular implants are not uncommon, but are almost always temporary. If needed, the implant can be exchanged or removed relatively easily. Of note, when performed in conjunction with a rhytidectomy, there does not appear to be any increased incidence of complication compared to rhytidectomy alone9. Infection risk for mandibular implants is extremely low, even using the transoral technique10,11. The risk of infection can be minimised even more with a meticulous sterile technique and the incorporation of gentamicin solution to bathe all instruments, the implant, and the subperiosteal pockets prior to implantation. It may also be helpful to place the patient on prophylactic antibiotics before and after the procedure. Over the past 18 years using intraoperative gentamicin, the author has not experienced any infections. If infection were to occur, an aggressive course of oral antibiotics is usually the first course of action. If persistent, however, it is common practice to remove the implant to eliminate the infection. If the implant were to be removed, which is rare, one may consider replacing the implant after a few months, if desired.

Sensory alterations are more common and are the most important negative sequelae of this procedure. Approximately 20% to 30% of patients may expect some hypoesthesia of the mental nerve distribution on one or both sides2. This hypoesthesia is almost always temporary. If the implant was placed properly, a period of observation for a number of weeks will herald the return of sensation to the numb area. Occasionally, longer lasting hypesthesia may be the result of improper dissection of the lateral pocket and placement of the implant superior to the mental nerve foramen. In that case, removal of the implant with or without replacement must take place.

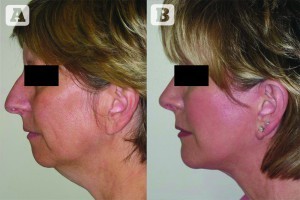

Figure 9 (A) Preoperative and

(B) postoperative images of a patient with microgenia and a dorsal nasal hump who underwent prejowl chin augmentation, rhinoplasty, and a rhytidectomy

Infrequently, the smile may be temporarily altered as a result of surgical trauma to the mentalis muscle. Furthermore, a very small percentage of patients may exhibit very temporary speech dysfunction postoperatively, usually intermittent lisping, secondary to the effects of swelling or bruising to the depressor muscles of the lip. While rare, a combination of hypoesthesia of the lip and injury to the mentalis or depressor muscles of the lip may cause temporary drooling and difficulty with proper enunciation. Motor nerve injury to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve is extremely rare and, if it occurs, is typically temporary.

Bone resorption of the outer mandibular cortex associated with chin augmentation implants has been well described12. The softer Silastic implants tend to resorb less bone than the firmer ones. Larger implants may cause greater absorption than smaller ones owing to the greater degree of pressure exerted on the bony cortex by the implant. Resorption tends to occur in the first 12 months, but is limited if the implant is properly positioned. The small amount of bony resorption that typically occurs is not expected to affect the soft tissue profile of the mentum. If the implant is removed, the area of bony resorption may regenerate to some degree.

Figure 10 (A) Preoperative and

(B) postoperative images of a patient with microgenia who underwent prejowl chin augmentation alone

Visual or palpable projections along the most lateral portion of the extended mandibular implants may occur because of capsular formation around the implant, or possibly as a result of infolding of the edge of the implant. This is especially true of the extremely thin, pliable edges of the extended anatomical chin implants. Frequently, gentle massaging over these areas will resolve the problem. The implant will rarely need to be removed and repositioned.

Asymmetry may occur owing to improper identification of the patient’s preoperative mandibular asymmetry or because of improper placement of the implant. The surgeon must be aware of any preoperative asymmetry and discuss this with the patient before the procedure. If asymmetry is caused by improper placement, the lateral pocket can be dissected and the implant repositioned with proper placement. The need for this is rare and has not been experienced by the senior author. Dislodgement of the implant is also extremely rare and has been reported in conjunction with mental nerve compression in one instance13.

Figure 11 (A) Preoperative and

(B) postoperative images of a patient with microgenia and a dorsal nasal hump who underwent chin augmentation with rhinoplasty and upper lid blepharoplasty

Conclusions

Mandibular contouring with an alloplastic implant is a very valuable tool, which allows the facial aesthetic surgeon to improve balance and restore youth to the patient’s jawline. While techniques and technologies are sure to evolve, alloplastic chin augmentation and prejowl augmentation have been readily established as safe and straightforward procedures. As illustrated in Figures 9–14, these procedures provide a tremendous amount of aesthetic improvement for a short and relatively easy surgery and recovery. Despite how well tolerated and low risk this procedure is, new implant materials may even further improve the risk to benefit ratio in the future.

Figure 12 (A) Preoperative and (B) postoperative images of a patient with microgenia who underwent prejowl chin augmentation with submentoplasty

Figure 13 (A) Preoperative and (B) postoperative images of a patient with microgenia who underwent prejowl chin augmentation with submentoplasty only (no face/neck lift) and lower-lid blepharoplasty

Figure 14 (A) Preoperative image of a patient with microgenia and a dorsal nasal hump, (B) a computer-generated prediction of postoperative results, and (C) a postoperative image of the patient after chin augmentation with rhinoplasty showing how close a result to computer imaging can be achieved. This series of images demonstrates that computer imaging can be a valuable tool in communicating surgical goals with a patient and that the final outcome may often closely approximate the computer‑generated image