Muscular enhancement in men is a rare request and reports in the literature about these operations are scarce. The necessary experience required to perform this kind of operation is difficult to acquire, but more and more men are seeking a solution to what they consider an aesthetic problem or a medical issue after an injury. In this article the author presents his experience of augmentation of a number of areas with silicone cohesive implants, including pectoral, buttocks, calves, biceps, triceps and deltoids. The author describes the implants that he prefers and the technique that has produced the best results. Before performing any of the procedures, the surgeon must be very conscious and knowledgeable about the anatomy and relationships between the nearby muscles and nerves.

At present, men are more conscious about their appearance: they consume more cosmetic products, sculpt their bodies in gyms, and even come to our offices for rejuvenation and body contouring procedures. However, while men train in gyms to achieve a certain aesthetic, sometimes the desired results are not reached — even with extensive training (and even with special diets or steroid abuse). One of the indications for body implants is to enhance the areas that do not respond to exercise.

In this article, the author reports on his experience of body implants in men, including ‘well known’ areas such as buttocks, pectoral and calves, and ‘rare’ indications such as deltoid, triceps, and biceps. After initial clinical experience with pectoral implants1, buttocks and calves, the author started to use cohesive (non-solid) silicone implants for muscular enhancement at other locations.

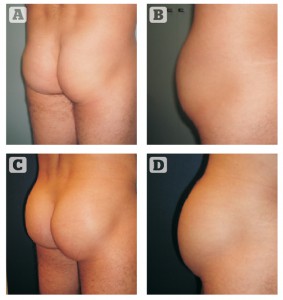

Buttocks

For most men, the author prefers oval implants, as it is important to enhance the muscle without feminising the area too much (Figure 1). Round implants are only used if the buttocks are very short (Figure 1). The author prefers to use Polytech Health & Aesthetics implants (Dieburg, Germany). Round implants provide a higher projection compared with oval implants (mean, 1 cm more).

The volume of the implant depends on the measurements performed. The pocket is limited between the iliac crest, trochanter, sacrum and a line drawn from the posterior iliac spine to the lateral edge of the gluteus maximus. Taking these measurements into account, the author chooses an implant that is 2 cm smaller to take into account the space inside is smaller than the surface. It is an extrapolation similar to one the author makes for breast implants. The author follows Vergara’s technique2, 3, which means intramuscular placement. The implants are placed in the upper two thirds of the buttocks.

The patient is placed in the ventral decubitus position, with a small pillow under the pelvis to flex the hips slightly. The muscles should be very relaxed so the author prefers general anaesthesia and the use of muscle relaxants. With the patient standing up the author marks the bony landmarks, such as the iliac crest, coccyx, and greater trochanter. The author then draws a line from coccyx to greater trochanter which is the caudal limit of the dissection. The markings are checked again, as they move slightly in relation to the bony landmarks.

A 7 cm incision is performed in the intergluteal sulcus, approximately 2–3 cm above the coccyx. An intact strip of skin, of 3–4 mm, is left in the centre of the incision. This strip is de-epithelialised and used to anchor the closing stitches. This prevents wound dehiscence, which is the main complication of the procedure in the author’s experience. A short tunnel is created under the skin and over the fascia to expose the gluteus maximus fibres. The author creates a window between the muscular fibres and creates an intramuscular pocket with blunt dissection, taking into account the need to leave enough thickness above the implant. It is very important not to make the pocket parallel to the surface (it should be oblique, following the axis of the pelvis, 30–45° downwards), as there is a risk of piercing the muscle at its lateral aspect, which may lead to extrusion of the implant into the subcutaneous area. Once both pockets have been created, the author checks the space and any remaining muscular fibre is broken bluntly or via electrocautery under direct vision using a lighted fibre-optic retractor. The implants are then placed. The author does not usually place drains he has have very rarely witnessed bleeding at the end of the procedure.

The muscle incision is tightly closed using 2-0 Vicryl sutures. The closure has to be perfectly performed to try and separate the implant from the subcutaneous and sacral tunnels completely.

The skin is then closed using 3-0 Vicryl sutures. The author then leaves a small, 8-French drain under negative pressure in the subcutaneous tunnel, which is extracted through a stab incision and never via the sacral wound. The interrupted subcutaneous stitches are anchored to the de-epithelialised strip of dermis left in the midline of access. Finally, the skin is closed with a buried, intradermal 3-0 Monocryl suture.

The wound is dressed and a girdle is placed. The patient is placed on antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs for 7 days. The patient can get up and sit 24 hours after the operation; however, she/he has to avoid the dorsal decubitus position for 5 to 6 days. Patients cannot exercise for 8 weeks and should wear a girdle at all times. After this period, they can resume normal activity.

Nine cases have been performed since 2009. In six patients oval implants were used and round for the rest. The smallest volume placed was 250 cc and the largest 350 cc. There was one complication (displacement), which required reoperation to reposition the implant.

Pectoral

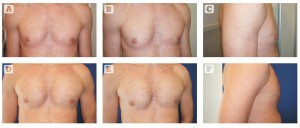

Figure 2 Pectoral implants, 190 cc (Polytech Health & Aesthetics, Dieburg, Germany). (A, B, C) Before and (D, E, F) after

The author performs a thorough evaluation to assess or measure the chest contour, the perimeter, asymmetries (different shape and volume of the muscles and width of each hemithorax), rib curvature, chondrosternal prominences and scoliosis. Physical evaluation is with the muscles relaxed and during contraction. Dynamic evaluation is very important because the muscles change in shape and length, and this has to be taken into account for choosing the proper implant.

Implants are available from Polytech Health & Aesthetics GmbH (Dieburg, Germany) and from Silimed (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Both manufacturers have three sizes available: 190 ml (width 14.4 cm, height 2.4 cm), 230 ml (width 15.8 cm, height 2.6 cm), and 300 ml (width 16.5 cm, height 2.9 cm). Implants from Polytech and Silimed are microtextured, while those from Silimed can be either textured or smooth. The incision made in the axilla is transverse for the manufactured pectoral implants and longitudinal, following the posterior aspect of the border of the pectoralis muscle, for the custom‑made implants. The mean length of the incision is 4 cm.

Similar to axillary breast augmentation, the initial dissection is subcutaneous and a 3–4 cm tunnel is made caudally. The lateral border of the muscle is identified and a pocket is created behind the muscle, initially with scissors and then with a blunt dissector. The muscle is never detached; otherwise, the implant will be positioned too low, resulting in a feminine appearance. Laterally, the author performs a blunt dissection to make room for the implant, stretching out the fascia to the width of the implants.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; e.g. ibuprofen) and antibiotics are given for 1 week. Compressive garments are not prescribed. Patients are instructed not to do any strenuous activity for the first 6 weeks. They can elevate the arm to stretch the muscles and the axilla. It is normal to feel tightness in the axilla for some weeks, until the scar softens.

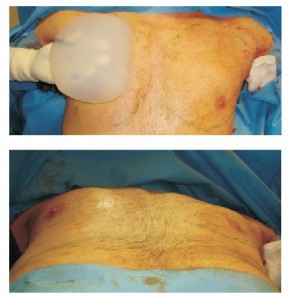

Figure 4 Intraoperative view of chest enhancement using a custom-made implant to get a more square look and define the whole contour

For most patients, commercially-available implants give a very natural profile and are enough for their expectations (Figure 2). In some cases, however, custom‑made implants are required. These implants comprise silicone elastomer and are less pliable. With them, it is possible to solve some requirements, such as filling the infraclavicular area (Figures 3 and 4).

The total number of patients treated in the author’s clinic for chest enhancement (excluding those with muscular injuries and Poland syndrome) has been 28 between 2003 and June 2010. In one case, the author placed 300 g implants. Eight patients had 190 g implants and in the remaining patients (16), 230 g implants were used. In three patients the author used custom-made implants. The main complication has been seroma, which affected four patients. In one patient with seroma there was bilateral infection and the author had to remove the implants.

Calves

Men who visit the author’s office usually complain of a lack of development despite intense training, and they see an imbalance between the well-developed thigh and their lower legs. In this area, the desire is to achieve well‑defined and contoured calves, and for that the author will need two implants for each leg in the majority of cases. Patients often want the maximum diameter possible.

The implant that the author uses for the medial gastrocnemius is anatomic shaped, designed by Montellano (Figure 5). This implant has more projection at its upper third, imitating the muscle. However, the author prefers the Glicenstein implant to enhance the lateral aspect of the leg. This implant is fusiform and symmetric, with maximal projection at its middle. The medial aspect of the leg is very shapely, with an upper convexity and a lower concavity. However, as the lateral gastrocnemius has less volume, the leg laterally has a gentle convexity.

In men that train heavily or follow special diets, the implants can be seen subcutaneously when placed in the classical plane, subfascially4, 5. The author now uses the submuscular approach more requently6. The wound is made at the posterior crease of the knee, the skin undermined and an incision is made at the fascia 4 cm lower to the skin incision. With a finger, the author identifies the border of the gastrocnemius and enters the space between this muscle and soleus. The pocket is made between them down to the Achilles tendon and between the midline of the leg and the edges of the bones (tibia and fibula). Care must be taken to avoid dissecting in the midline, where the sural nerve is located.

The chosen implant depends strictly on the length of the pocket, which is positioned between the incision at the fascia and the most caudal limit of the pocket.

The patient can start walking with crutches the next day. Painkillers and sometimes muscular relaxants are needed, especially when two implants are placed. It is very important to watch out for any sign of ischaemia or compartment syndrome. Sometimes the patient may feel paresthesia and sensory disturbances that resolve spontaneously.

The author treated 11 male patients between 2009 and 2012, as follows:

- Group I: patients who complained of a lack of volume at the medial aspect of the leg and did not want a big augmentation. One patient with Glicenstein (symmetric) implant, 90 cc, subfascial

- Group II: atrophy owing to neurological problems, sequelae of poliomyelitis or previous foot operations. Four male patients. Three patients needed two implants (medial and lateral). In one patient tissue expanders were used under both muscles and these were replaced by one 500 cc oval implant for medial contour and one Glicenstein implant, 90 cc, for lateral contour

- Group III: six patients, all male. Two of them had only medial enhancement with one implant (submuscular in both cases). The other four patients had two implants in each limb, submuscular in two patients and subfascial in the remaining two.

Figure 5 Calf augmentation, submuscular. Two implants in each leg (Montellano medial

of 140 cc and lateral of 85 cc). (A, B) before and (C, D) after

Results are very good with both subfascial as submuscular (Figure 5) techniques. However, the author believes that the result is much more natural with submuscular placement and the edges of the implants cannot be seen (especially in those patients who follow particular diets to define and lose a lot of subcutaneous fat). However, the immediate postoperative course is slightly more painful.

Deltoid

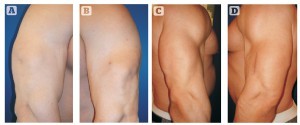

Figure 6 Deltoid augmentation, 110 cc oval (A) and (B) before treatment; and )C) and (D) after treatment. The new contour is seen with the arm adducted, and remains natural when abducted, without unduly and obvious convexity

This triangular muscle attaches proximally at the external third of the clavicle, the acromion and the scapular spine. The fibres of this muscle are responsible for the roundness of the shoulder and join together distally at the deltoid V, where they are attached to the humerus shaft. Its innervation depends on the axillary nerve, which enters the deltoid posteriorly after leaving the quadrilateral space.

The surgeon should approach the muscle from its anterior side. The incision is made at the anterior edge of the deltoid V, at the groove between the deltoid and biceps. The incision is deepened to the bone and a pocket is made by blunt dissection. The pocket has to be wide enough to accommodate the implant.

For this location, a smooth, oval implant can be used, and the author prefers a volume of 110 cc (Figure 6). This implant has a similar shape to the muscle and the tip of the implant will be under the deltoid V. No drains are used. The muscle fibres are sutured with 2-0 Vicryl and the incision is closed.

The primary potential problem with this muscle is implant displacement. The space is tight, the floor of the pocket is convex, and the implant might be unstable with the movements of the arms.

The author has performed three cases of deltoid implants to date (six implants in total). The volume of the implants was 100 cc in all cases. In one of the patients, one of the implants displaced and required surgical repositioning and reinforcement of the anterior wall of the pocket with a mesh.

Triceps

The triceps has three heads, namely the long, medial and lateral heads, that converge distally forming a tendon that inserts into the olecranon. The radial nerve groove is closely related to the muscle, so extreme care is needed to avoid injuring it.

The incision may be made at any of the sides of the triceps tendon, and the dissection is deepened under the tendon and muscle. A careful blunt dissection is performed under the long head of the triceps and is expanded medially and laterally. Blunt dissection avoids inadvertent rupture of any nerve branch crossing the muscle. It is recommended that no muscle relaxants be used by the anaesthesiologist so that the surgeon is able to check any muscular movement in the vicinity of the radial nerve. In most cases, the author uses oval buttock implants, 110–240 cc, depending on the available pocket (Figures 7 and 8). In some cases, where there are atrophied or very thin muscles, it is best to use Montellano implants (Figure 9).

The author has performed four cases to date. One case was a 26-year-old patient with a left brachial plexus injury as a result of a traffic accident. He had radial and circumflex palsies. A 140 cc Glicenstein implant was placed under the muscle. The second case was a 32-year‑old male patient who sought muscular enhancement. A 215 cc oval implant was placed under the muscle bilaterally. The third case was a 44-year-old patient with a muscular injury on the left arm owing to excessive weight lifting (the lateral portion was broken and atrophied thereafter). A 215 cc oval implant was placed under the injured muscle to achieve symmetry. The fourth case was a 27-year-old male seeking muscular enhancement. In that case a 110 cc oval implant was placed.

Biceps

Figure 8 32-year-old male patient with injury (rupture) of his left triceps muscle. Preoperative view: normal (A) versus injured arm (B). Postoperative view at 8 months: normal (C) versus injured arm (D)

This muscle has two heads with the long one attaching proximally to the supraglenoid tubercle and the short one inserting at the coracoid process. Both heads attach through a tendon distally at the radius. Innervation comes from the musculocutaneous nerve that runs between the brachialis and the biceps tendon.

The pocket can be either made from proximal or distal incisions. A tear is performed in the muscle fibres and the pocket is made bluntly between the biceps and the brachialis. The nerve can be seen at the medial half of the muscle, leaving the coracobrachialis at the junction between the upper and middle third of the muscle. The blunt dissection should be continued upwards while taking care not to stretch the nerve.

The best implant to place here is the oval buttock implant with a volume of 110 cc or 240 cc depending on the width of the arm (Figure 10). If the biceps width is less than 8 cm the author uses Montellano implants. The tip of the implants are placed cranial to the muscle and medial to the nerve.

Figure 9 (A) Montellano implant for triceps reconstruction. Muscular atrophy secondary to brachial plexus injury: (B) before and (C) postoperative result with Montellano implant (140 cc)

The author has performed five cases to date. The first case was a 22-year-old male patient, in whom a subfascial, 90 cc Glicenstein implant was used to enhance the contour. The result was less than satisfactory owing to migration of the implant when flexing the elbow. In the remaining patients (26-, 33-, 49- and 28-year-olds), the author used oval implants (110, 240, 110 and 110 cc respectively) under the muscle. The postoperative course was uneventful in all cases.

Discussion

Other than the breast, most surgeons worldwide have only experience with buttock, pectoral and calf implants. Patients requesting enhancement at other locations are rare, so it is very difficult to acquire a long series of patients for these regions during the normal course of a surgeon’s life. However, with anatomical knowledge and currently available implants, it is now possible to reconstruct or enhance the contour in certain areas.

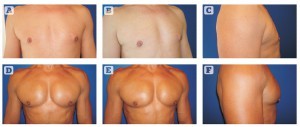

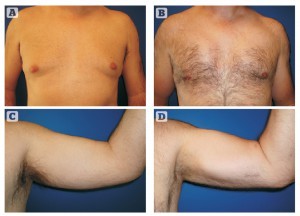

Figure 10 45-year-old patient. (A, C) Pre- and (B, D) postoperative view after gynaecomastia treatment plus pectotal implants (190 cc) and biceps implants (110 cc oval)

Hodgkinson7 described some patients with nerve or muscular injuries that caused contour problems, which he solved using solid silicone implants. The main advantage of these implants is that the surgeon can restore the contour because a moulage from the healthy side is used. However, they are more expensive and take longer for the manufacturer to make. To the author’s knowledge, there are no reports in the available literature about using cohesive implants for muscular limb enhancement. In his experience, commercially available implants can be used safely in these patients. Implants are made of cohesive silicone gel, have the advantages of rapid availability and softness, and can accommodate muscular contraction and relaxation. The only potential problem is that we do not know whether the implant will wear out in the long term owing to shearing forces.

Incisions for implantation are made, in most cases, at the natural grooves of the muscles. In the case of injuries, the old scar can be used for placement, but for other cases, a 4–5 cm incision is enough to make the pocket and to place the implant. Unlike Hodgkinson, the author does not use a transverse incision over the triceps tendon, but prefers a longitudinal incision following its edge.

The author also does not use solid implants. Cohesive silicone implants behave well in these situations. They are strong enough to maintain a natural shape and are sufficiently elastic to allow normal activities, even in strenuous situations like fitness and muscular training.

The main complication so far has been displacement (one case of buttock augmentation and one case of deltoid enhancement). These patients needed reoperation to replace the implant and reinforce the pocket. After this kind of operation, it is paramount not to train the muscles for at least 6 weeks. The author uses ultrasonography to check the position of the implant and movement in a dynamic evaluation. A closed ‘surveillance’ must be carried out in these patients and if needed, they should visit the office once per week. After this period the patient can resume normal activity. There are no restrictions with regard to training and exercise.

The buttocks behave very well. Although it is quite painful in the first few days, the author has not experienced any seroma, haematoma, or infection using the intramuscular (Vergara’s) technique. Temporary sciatic nerve compression with pain can happen in some patients as the lower edge of the implant is located over the sciatic foramen. The intramuscular technique prevents the placement of the implant directly on the nerve; however, postoperative pain and Lasègue’s sign that some patients experience shortly after the operation seems to be related to the tension of the muscle and the extra volume caused by the surgical haematoma. It is self-limited and can be treated with NSAIDs (e.g. ibuprofen 600 mg three times per day) and relaxant drugs (e.g. metocarbamol 380 mg three times per day).

Calf implants are also quite safe, though in the author’s experience lateral implants tend to displace upwardly, owing to the lack of space when two implants are placed. Most complications are related to minor compression of sensitive nerves that are self-limited. The worst complication that one might see is compartment syndrome, because it might produce muscular necrosis and Volkmann syndrome, with severe aesthetic and functional sequelae.

The author has not experienced any case of seroma for any implant, other than pectoral augmentation. A small amount of periprosthetic fluid is normal and is usually found at areas where the implant is slightly wrinkled. In a previous article1, the author reported not a single case of seroma in 18 patients with pectoral enhancements for aesthetic reasons. In the following ten patients, however, there have been four cases. This was related to a change in implant manufacturing. In the author’s opinion, seroma was caused by rubbing of the implant surface with the muscle. For this reason, Polytech changed the shell of pectoral implants to microtextured. Silimed has smooth implants available. Hodgkinson7 reported 30% of seroma cases and claimed to reduce that incidence by careful dissection and the use of NSAIDs. Pereira et al8 reported the occurrence of three seromas out of 16 patients with calf augmentation.

Conclusions

To ensure success with muscular enhancement using implants, the author suggests following these broad recommendations:

- Choose an implant that properly fits the pocket and muscle size. Avoid using an oversized implant

- Choose a microtextured or smooth implant

- Give a thorough explanation to the patient of the pros and cons of the procedure as well as insisting on resting during postoperative weeks (5–7 weeks)

- Do not detach the muscle boundaries. Keep in mind the anatomy of the muscle.